The Gift of Presence

This week we welcome back Dr. Russell Jeung to the blog for the fifth of a six-part series on Asian America. Russell Jeung is Professor of Asian American Studies at San Francisco State University and co-Founder of Stop AAPI Hate. In 2021, he was named one of the TIME 100 most influential people in the world. Find the full series at the bottom of this article.

“When you pass through the waters, I will be with you; and when you pass through the rivers, they will not sweep over you. When you walk through the fire, you will not be burned; the flames will not set you ablaze.” - Isaiah 43:2 The cultures and backgrounds of Asian Americans, I submit, make us attuned and receptive to particular expressions of God’s love. For instance, I’ve written how Asian Americans like myself can see God’s hesed, faithful love modeled in how our elders devotedly take care of one another. We receive grace in the honor and favor that our loved ones confer on us. And we taste God’s love when we’re fed, both physically and spiritually, by our guardians and the Rice of Life.

Both our heritages and our specific love languages, then, are gifts of God to Asian Americans.

In the Parable of the Prodigal Son, the shamed younger son returns to accept the Father’s love showered on him in the ways mentioned above. When the elder son resentfully complains about the favored treatment of his brother, the father rebukes him. The father shares that he has loved the elder son in another, special way: ‘”My son,” the father said, “you are always with me, and everything I have is yours.”’

The father loved his elder son with his presence. In an Asian American way of communicating without words or gestures, the father still was expressing his deep love by the gift of simple, yet deeply attached presence.

Proponents of attachment theory like Dr. Joan Jeung, UCSF Professor of Developmental Pediatrics and my highly esteemed wife, observe that babies need the presence and nurturance of caretakers in order to develop physically and emotionally. Strong attachments formed by the proximity and responsiveness of guardians form the basis for future, trusting relationships throughout one’s lifetime, as well as a host of other benefits. Those who experience adverse childhood experiences, such as abuse or family addictions, especially need the presence of a caring adult in order to build resilience.

The remarkable gift of presence, by way of proximity and responsiveness, thus establishes and communicates a love that lasts a lifetime.

Unfortunately, in our hyper-individualized, mobile and virtual society, the gift of presence can easily be devalued and lost. Like the eldest son in the parable, my foster daughters have felt abandonment and estrangement. They have gone through much hurt and trauma in their lives—losing their parents and having to leave their homeland due to religious persecution. They arrived in the US with just backpacks, feeling very alone in this new society.

My eldest daughter often describes her sadness during discouraging times as feeling “small.” I can understand how this petite young woman from a small, rural village in Burma could feel tiny, especially when considering the vast, fast-paced urban metropoles where she was treated as anonymous and insignificant.

My daughters quickly learned to be independent, as is the American way, but not necessarily attached and interdependent.

Yet, what I want my daughters and my son to know is that as their father, I will always be there for them. That they are not alone and that even if they were physically apart, that I’m thinking of them. If they ever were to need me, I’d drop everything to go to them. As the Jackson 5 sang, “Just call my name, and I’ll be there.” My love is to be for them, with them.

In the same way, being together as a family on holidays or key events is often the highest priority of Asian Americans and their most significant annual ritual. I had to be at the restaurant when my aunt came to town. It’s assumed that I would attend Christmas Eve dinners. Everyone’s presence so that families could be together, in fact, is the primary reason for these lasting ethnic traditions.

From this model of family togetherness, I’ve come to know how showing up for church family is one of the ultimate reasons of God’s will and for my own being. Jesus came as Emmanuel, God with us, to restore our very purpose as God’s creation and to repair our communion with God. Jesus showed up to make a new people, reflecting the unity of the Trinity. Being present—together with others—constitutes our very essence as God’s family of God.

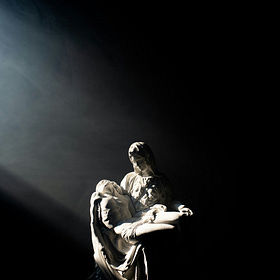

In my darkest moments or times of deepest grieving, I have cherished the presence of family and friends. Even though their company didn’t lessen my pain, their showing up did make me feel less alone. Their accompaniment while I went through the waters made suffering at least bearable. This expression of love became all that I could hold on to, in that even in the fire I still could count on God’s abiding, ever-present love.

Asian American Christians, let’s nurture attachments as strong as a nursing mother to her infant. May we show up for our community, especially in the times of struggle and trial. Let’s be present to one another and to a broken world.

Dr. Russell Jeung is a sociologist and professor in the Asian-American Studies Department at San Francisco State University. He received a B.A. in Human Biology and a M.A. in Education from Stanford University. After working in China and in the Mayor's Office of San Francisco, he obtained his Ph.D. in Sociology from the University of California, Berkeley in 2000. In 2020, Dr. Jeung launched Stop AAPI Hate, a project of Chinese for Affirmative Action, the Asian Pacific Policy and Planning Council, and SF State Asian American Studies. It tracks Covid-19 related discrimination in order to develop community resources and policy interventions to fight racism.

Asian American Gifts to the Church Series

Introduction to Asian American Gifts to the Church

Asian American Christians may not see themselves as a distinct community with racial and cultural traits, but I believe that God has indeed given us specific gifts as a group. Let me start by explaining why identifying our collective blessings is relevant and so necessary.

The Gift of Hesed

This love was unconditional. She cared for him devotedly even when he couldn’t respond with affirmation because he couldn’t speak. He couldn’t offer physical touch since he couldn’t move. The time spent together must have been lonely and sad; it wasn’t the “quality time” of which Chapman wrote.

The Gifts of Blessing

When the prodigal son returns, the father erases the shame by restoring the blessing that their relationship confers. He authorizes his servants to dress him with a robe, just as Joseph had received from Jacob, symbolizing the father’s favor. The son receives a ring indicating he has the father’s power and authority over household affairs. And he is shod with sandals that reflect his family status within the home, as compared to the servants who remained bare-footed. (This point defies the general Asian American experience, as no self-respecting Asian would wear shoes in the house).

The Gift of Dim Sum

My family took Saturday excursions to Chinatown to shop, to join youth groups, to work at my father’s office, and mostly, to eat. Although I would occasionally go off on my own to get a cheeseburger, my father especially loved having the entire family go out for yum cha (drink tea) in order to enjoy dim sum (lightly touching your heart) dishes such as chive dumplings or steamed spare ribs with black bean. He lived to eat.

The Gift of Presence

From this model of family togetherness, I’ve come to know how showing up for church family is one of the ultimate reasons of God’s will and for my own being. Jesus came as Emmanuel, God with us, to restore our very purpose as God’s creation and to repair our communion with God. Jesus showed up to make a new people, reflecting the unity of the Trinity. Being present—together with others—constitutes our very essence as God’s family of God.

The Gift of Sacrifice

Having experienced sacrifice as a love language, I think we Asian Americans can understand God’s sacrifices for us in ways that others may not so readily grasp. With these parental models of sacrifice, we recognize that we can never repay or reciprocate what we have received. Instead, in order to convey our love in return, we earnestly work to make them proud and to be able to take care of them when we can.