This week we welcome back Dr. Russell Jeung to the blog for the second of a six-part series on Asian America. Russell Jeung is Professor of Asian American Studies at San Francisco State University and co-Founder of Stop AAPI Hate. In 2021, he was named one of the TIME 100 most influential people in the world. Find the full series at the bottom of this article.

“Though the mountains be shaken and the hills be removed, yet my unfailing love for you will not be shaken nor my covenant of peace be removed,” says the Lord, who has compassion on you.” --Isaiah 54:10The Five Love Languages, according to the best-selling marriage book by Gary Chapman, are “fundamental ways of expressing love that are universal.” They include communicating love through ways such as affirmation, quality time, and physical touch.

When I first heard about the five love languages, I felt as if I were a mute regarding love. My Chinese American family didn’t communicate love in such manner. Who ever heard of an Asian tiger mom affirming her daughter for a B+, or a hard-working, Asian dad take time from his business to spend precious, free hours to take his son to a ball game?

I’ve realized since that the Five Love Languages are not the only fundamental, universal ways to express love. Rather, European Americans often write as if their ways are normative for all, or that their interpretations of Scriptures are orthodox. Clearly, the Five Love Languages are helpful ways of communicating affection, but I believe God has also gifted Asian Americans with five, other love languages.

These Asian American love languages include the ways in which I’ve seen my family communicate their deep love, as well as the manner in which God the Father demonstrates divine love. The Parable of the Prodigal Son, for instance, illustrates all five.

The first Asian American love language is hesed: faithful, loyal love. In the passage, the prodigal son had spent a long time going afar, squandering his wealth, and enduring a famine. When he finally returned, the father saw him from a long way off, as if he had been patiently, longingly waiting for his lost son. The father, filled with compassion, ran toward his son without shame or reservation, and hugged him. Despite the son’s scorn and betrayal, the father welcomed him gladly. While his son wished him dead so that he could gain an inheritance, the father always held on to their relationship.

This long-suffering, never-ending love is how I’ve witnessed my family care for each other. When my father suffered a stroke and remained in the hospital, my 79 year old mother took the bus to visit him daily—for almost an entire year.

My uncle also had a stroke, became paralyzed, and eventually, unable to communicate or respond. Nevertheless, my aunt refused to place him in a nursing facility, but took care of him on her own and rarely left his side. Daily, she fed, bathed, and changed his diaper. Nightly, she awoke to roll him over so that he wouldn’t get bedsores.

This love was unconditional. She cared for him devotedly even when he couldn’t respond with affirmation because he couldn’t speak. He couldn’t offer physical touch since he couldn’t move. The time spent together must have been lonely and sad; it wasn’t the “quality time” of which Chapman wrote.

Yet for over three years, my aunt loved my uncle with such fierce loyalty. I’m still in awe of the patient loyalty that she demonstrated. While I’m sure she must have been discouraged at times or wanted to give up, she stuck with him.

And these are the ways the Father loves us.

Such covenantal love assumes that the relationship will always be a constant. Just as I know that my wife and family will always be for me, I can rest in the knowledge that God will be ever faithful.

Obviously, other cultures display this kind of love and can resonate with the generous Father’s devotion to the prodigal son. I’m suggesting, however, that Asian Americans like myself may relate to God’s love in this way because we have concrete role models of such enduring commitment in our upbringings.

Having been loved with faithful loyalty, we Asian Americans can offer this gift to our congregations. When others increasingly view church membership as an individual, optional choice, Asian Americans might take their roles and responsibilities in the community as givens—we are part of a body, so we are always to take into account the relationships within the body.

This hesed love can show up in other relationships as well. Within our marriages and families, at work and in community organizations, stable commitments to the collective aren’t often recognized but are critical. Because we are loyal, we can be counted upon as trustworthy.

Since childhood, I’ve long had the blessed assurance that God is ever with me and will never forsake me. That’s an Asian American love language I’ve received from my family, and that’s how I share my love, I hope, to my kids.

Dr. Russell Jeung is a sociologist and professor in the Asian-American Studies Department at San Francisco State University. He received a B.A. in Human Biology and a M.A. in Education from Stanford University. After working in China and in the Mayor's Office of San Francisco, he obtained his Ph.D. in Sociology from the University of California, Berkeley in 2000. In 2020, Dr. Jeung launched Stop AAPI Hate, a project of Chinese for Affirmative Action, the Asian Pacific Policy and Planning Council, and SF State Asian American Studies. It tracks Covid-19 related discrimination in order to develop community resources and policy interventions to fight racism.

Asian American Gifts to the Church Series

Introduction to Asian American Gifts to the Church

Asian American Christians may not see themselves as a distinct community with racial and cultural traits, but I believe that God has indeed given us specific gifts as a group. Let me start by explaining why identifying our collective blessings is relevant and so necessary.

The Gift of Hesed

This love was unconditional. She cared for him devotedly even when he couldn’t respond with affirmation because he couldn’t speak. He couldn’t offer physical touch since he couldn’t move. The time spent together must have been lonely and sad; it wasn’t the “quality time” of which Chapman wrote.

The Gifts of Blessing

When the prodigal son returns, the father erases the shame by restoring the blessing that their relationship confers. He authorizes his servants to dress him with a robe, just as Joseph had received from Jacob, symbolizing the father’s favor. The son receives a ring indicating he has the father’s power and authority over household affairs. And he is shod with sandals that reflect his family status within the home, as compared to the servants who remained bare-footed. (This point defies the general Asian American experience, as no self-respecting Asian would wear shoes in the house).

The Gift of Dim Sum

My family took Saturday excursions to Chinatown to shop, to join youth groups, to work at my father’s office, and mostly, to eat. Although I would occasionally go off on my own to get a cheeseburger, my father especially loved having the entire family go out for yum cha (drink tea) in order to enjoy dim sum (lightly touching your heart) dishes such as chive dumplings or steamed spare ribs with black bean. He lived to eat.

The Gift of Presence

From this model of family togetherness, I’ve come to know how showing up for church family is one of the ultimate reasons of God’s will and for my own being. Jesus came as Emmanuel, God with us, to restore our very purpose as God’s creation and to repair our communion with God. Jesus showed up to make a new people, reflecting the unity of the Trinity. Being present—together with others—constitutes our very essence as God’s family of God.

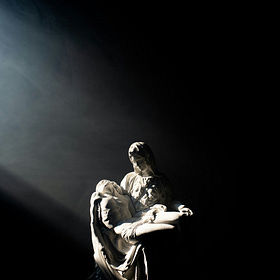

The Gift of Sacrifice

Having experienced sacrifice as a love language, I think we Asian Americans can understand God’s sacrifices for us in ways that others may not so readily grasp. With these parental models of sacrifice, we recognize that we can never repay or reciprocate what we have received. Instead, in order to convey our love in return, we earnestly work to make them proud and to be able to take care of them when we can.