"We are dying, we are suffering, we are socially isolated..."

The Hidden Toll of Filipino Nurses During COVID

By the Center for Asian American Christianity at Princeton Theological Seminary.

On Friday, April 11, the Center for Asian American Christianity at Princeton Theological Seminary hosted Healing Heritage: Stories of Faith, Selflessness, and Service of Filipino Nurses, a powerful hybrid event that brought together healthcare workers, scholars, clergy, and community leaders to explore the intersections of faith, healthcare, and the Filipino diaspora. The event centered on the lived experiences of Filipino nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic, offering a space to reflect on their spiritual resilience, communal values, and the systems that continue to render their labor invisible.

The conference is part of a growing, multi-institutional research initiative led by Dr. Aprilfaye Manalang, Associate Professor at Norfolk State University. What began as a local project in the Virginia Beach/Hampton Roads region—home to one of the largest Filipino communities in the American South—quickly grew into a national and transnational collaboration. Co-investigators Dr. Christian Gloria (Columbia University Medical Center) and Dr. David Chao (Princeton Theological Seminary) joined Dr. Manalang in building one of the most comprehensive projects to date on the resilience of Filipino nurses under the COVID-19 pandemic through their religious beliefs and faith practices.

Racial Capitalism and Disposable Migrant Labor

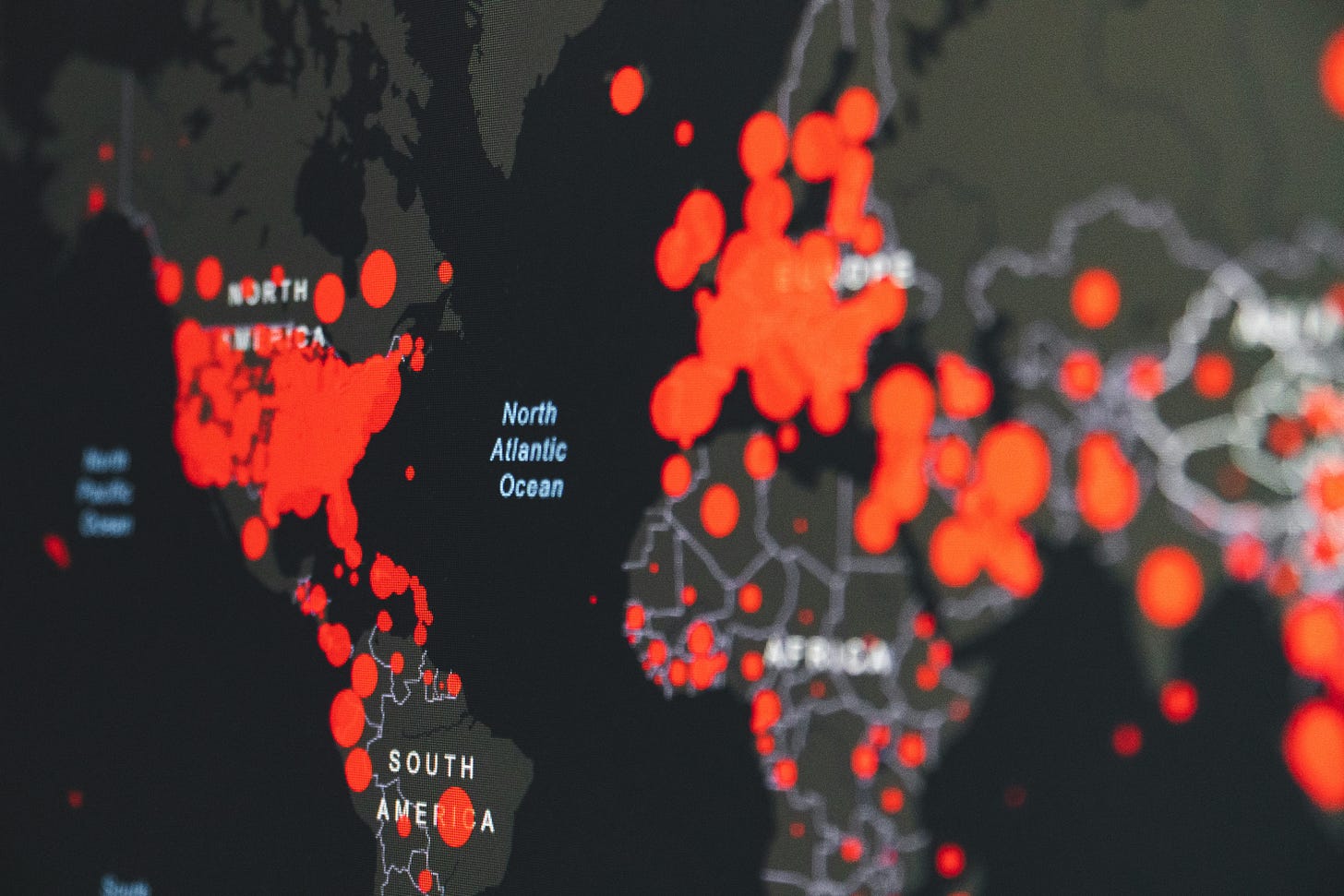

A sobering reality motivated this event: although Filipino nurses make up only 4% of the U.S. nursing workforce, they accounted for approximately one-third of nurse deaths in the early months of the pandemic. This staggering statistic points beyond disproportionate exposure to a deeper structure of racialized labor and global inequality. In her opening remarks, Dr. Manalang recalled stories of Filipino nurses who felt overwhelmed, alone, and forgotten—many of them forced into precarious, risky, and vulnerable situations. "We are dying, we are suffering, we are socially isolated," one nurse told her.

These stories are helpfully understood through the framework of racial capitalism. Constructive theologian Jonathan Tran, in Asian Americans and the Spirit of Racial Capitalism, argues that racial capitalism involves the racialization of migrants from Asia to perform disposable labor. Filipino nurses, especially women, exemplify this logic. The history of colonial occupation, militarization, and authoritarian labor export policies—especially under Ferdinand Marcos in the mid-late 20th century—has rendered the Philippines a major exporter of healthcare labor. Filipina nurses are often recruited globally to fill high-risk, low-recognition positions in the healthcare sector.

Indeed, Filipina scholar Neferti X. M. Tadiar describes Filipino nurses and care workers as embodiments of "global disposable life"—a surplus population shaped by centuries of colonial extraction, militarized displacement, and economic restructuring. When these nurses migrate to countries like the U.S., they enter new cycles of disposability. U.S. healthcare systems depend on their labor while offering inadequate protection. During the pandemic, many were overworked, denied personal protective equipment, and expected to continue laboring through illness and grief.

Stories of Struggle, Stories of Faith

Dr. Christian Gloria added insights from his research, where Filipino nurses faced immense pressure to keep serving despite personal risks. Many contracted COVID-19; some lost their lives. His presentation underscored a recurring theme: these nurses were navigating a dual crisis—protecting their patients while confronting their own emotional and physical vulnerability.

Maria Theresa Largo and Aimary Rubio presented initial research findings based on interviews with Filipino nurses across the U.S. and the Philippines. The nurses they interviewed shared stories of workplace bullying, psychological exhaustion, and limited institutional support. Yet alongside these stressors, Largo and Rubio found deep reservoirs of spiritual resilience. Nurses described both public and private religious practices, from broadcasting novenas (a nine-day prayer liturgy) over hospital intercoms to quiet, personal prayers before making difficult medical decisions. For some, the pandemic rekindled a faith they had not previously considered central to their lives.

Hans Carlo Rivera brought additional depth to the conversation through multiple interview excerpts schowcasing the audible voices of Filipino nurses. Many spoke of praying the rosary, trusting God to protect their families, and using faith to sustain a sense of hope. These expressions of belief were not merely personal; they were profoundly cultural. Cultural sacred values like utang na loob (a deep sense of mutual obligation) shaped an ethic of care that transcended duty.1 Rivera also situated these testimonies within a longer history of labor migration and colonial subjugation, challenging listeners to see these nurses not as passive victims but as powerful agents of communal care and resistance against a larger global structure of exploitation.

Looking Ahead: Solidarity and Structural Change

Dr. David Chao concluded the event by urging theologians and church leaders to confront the false divide between the sacred and the secular. Immigration policy, labor exploitation, and racialization, he argued, are not merely political issues—they are deeply theological and thus demand a Christian response. The sacrificial labor and spiritual tenacity of Filipino nurses pose urgent questions for Christian ethics, public theology, and institutional accountability.

The final Q&A session opened up further reflection on generational differences among Filipino nurses, the persistence of indigenous belief systems, and the economic pressures that compel nurses to remain silent in the face of exploitation. Panelists named the systems that uphold this silence: remittance economies, visa precarity, and internalized cultural expectations to endure rather than resist. In robust conversation, audience members contributed their experiential understanding of the on-the-ground sources of dysfunction for Filipino nurse immigrants.

Ultimately, Healing Heritage was more than a moment of storytelling—it was a call to structural and spiritual transformation. It challenged attendees to rethink the theological, economic, and institutional frameworks that render essential workers both indispensable and invisible. It reminded us of our complacency and gifted us growing awareness of the implications of the global pandemic. It was a collective affirmation that God is not confined to sanctuaries or seminaries, but is palpably present in hospital corridors, break rooms, and whispered prayers. In bearing witness of these marginalized and exploited Filipino nurses, the event called on all of us to do more— to act and to seek justice.

The Center for Asian American Christianity at Princeton Theological Seminary advances the scholarly study of Asian American Christianity, develops a forward-looking vision for Asian American theology, and equips and empowers Asian American Christians for faithful gospel ministry and public witness.

See Manalang, Aprilfaye (2016). Religion and the “Blessing” of American Citizenship: Political and Civic Implications for Post-1965 Filipino Immigrants. Implicit Religion, 19(2), 283-306.