My Hero, Lee Won Geun (이원근) Part 2

Remembering sacrifice and discipline from the Korean Christian community

By Joseph Cho, an incoming master's student at Emory's Candler School of Theology.

Originally published in "The Jo Cho Show" on Substack, this testimony was delivered at Epic Church’s Sunday service on May 5, 2024. For an audio version, Jo recommends the recordings on Epic Church’s Soundcloud page. For the first half of the essay, go to:

When I left home for USC, I decided to leave my childhood church behind. I couldn’t put words to my trauma and oppression, but I knew I couldn’t keep living in fear. And when I realized that I had suffered abuse, I developed a deep resentment towards the Korean American Christian community.

For the longest time, I preferred being a minority to being part of another Korean space where my people despised me and pushed me to the margins. It seemed that the only thing the community had to offer was sanctimonious propaganda about our forefathers’ prayer lives. But where was that religious conviction when vulnerable people like me were being oppressed in their own backyard?

It felt like Korean people had nothing good to offer to the world.

…

I was wrong.

In my junior year of college, I decided it was time to reclaim my family story. It helped that I was taking a family history class and it helped that my family included diaspora people in North America who could speak English. Two of my uncles from this side, Uncle 경섭1 and Uncle 경준2, introduced me to a memoir of our family hero.

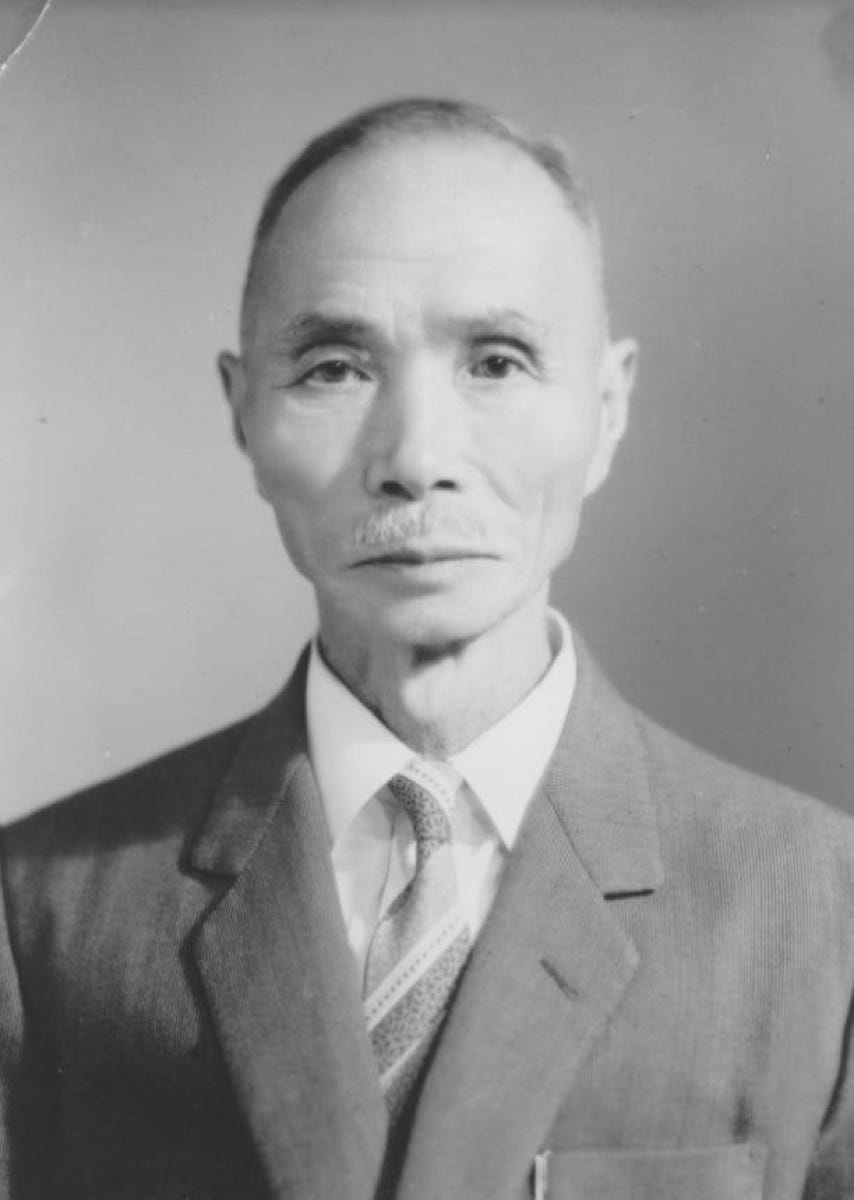

Enter my Great Grandfather: 이원근.

At first, Great Grandfather read to me as the classic pious patriarch. The memoir praised him for studying the Bible diligently, praying ceaselessly, and refusing to compromise the teachings of the Bible. But it also added something unexpected: he was also an independence hero.

Great Grandfather was about my age when the Japanese government decided to colonize Korea. He wasn’t a soldier, but he decided to fight back the best way he knew how. During the March 1st Independence Movement, he was part of a group plotting to write and deliver a letter exposing police brutality against political prisoners.

For that, he paid the price: six months of prison, torture, and inhumane living conditions.

But Great Grandfather refused to allow Empire to break his spirit.

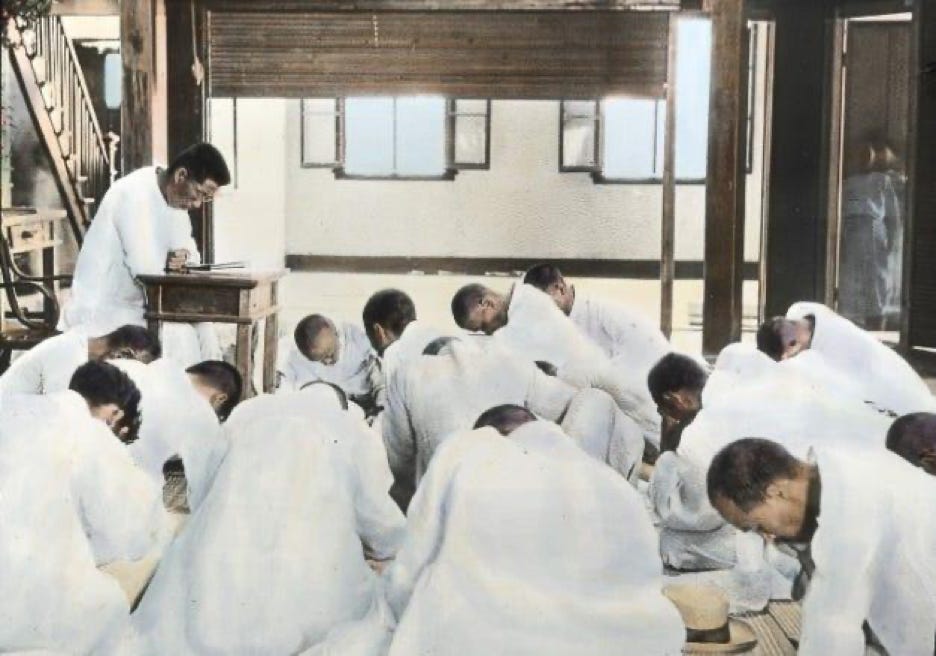

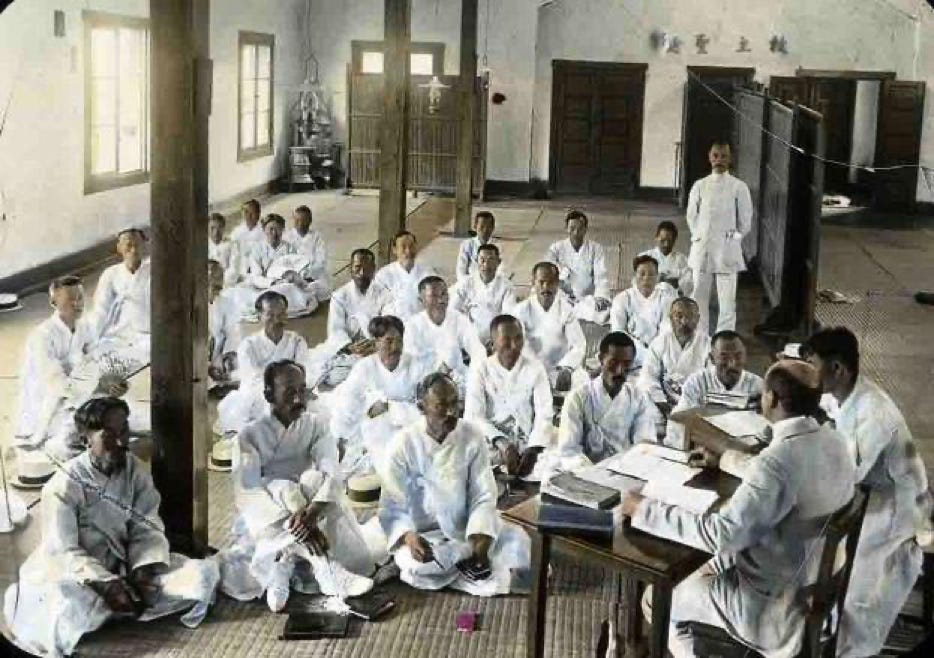

Every evening, he gathered all the Christians in the prison together to hold secret worship services. Because he had memorized hymns, the Gospels, and the Book of Acts, he could give sermons inspiring the prisoners to keep the faith.

As a result, the memoir says that “the ward was always filled with God’s presence and comfort” because the prisoners had something to look forward to every day.

But Great Grandfather’s courier work or jail stories were not the highlight of his resistance. For Uncle 경섭, that happened almost twenty years later, when he refused to bend the knee to State Shinto.

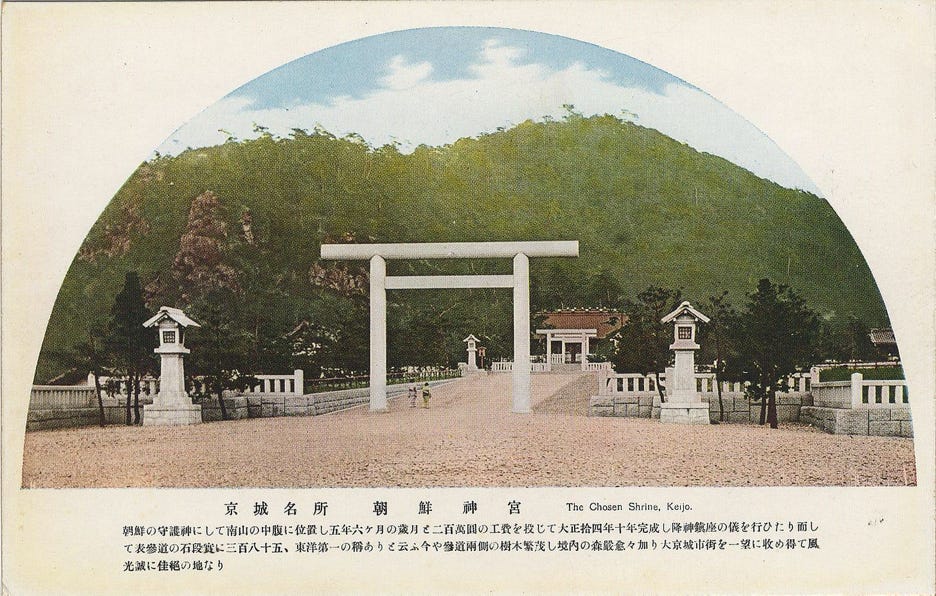

State Shinto was the Japanese government’s perversion of the Shinto folk religion to justify its own power. Its god was Tennō-heika, the emperor of Japan. In the 1930s, State Shinto became part of the plan to assimilate Koreans as loyal imperial subjects.

Uncle 경섭 remembers that every morning, the colonial authorities forced Koreans to visit Shinto shrines and recite liturgy worshipping the emperor. They would have to bow down to Japanese war gods and emperors who tried to conquer Korea, which meant denying their Koreanness.

In this context, any other god than Tennō-heika was a threat to national security. Jesus was seen as especially subversive. Uncle 경섭 remembers that the colonial authorities seized all the hymnbooks and blotted out every line saying that Jesus was King.

It is too easy to say that Christian resistance to State Shinto was a no-brainer. But the reality was far more complex: most Christians were willing to bend the knee.

The American missionaries who had sponsored Korean Protestants actively discouraged independence efforts. In fact, they actually told the Koreans to comply with mandatory shrine worship, telling them that it was just another cultural practice of the lawful authorities. In reality, they feared that speaking truth to power would jeopardize their influence over the Korean people.

Many Japanese Christians weren’t much better. Even in the 1910s, the Japanese Congregational Church launched a series of missions called “kyusai doka” to “save and assimilate” Koreans from their Koreanness. They too were fearful of persecution, so they tried to align themselves with the nationalism of Japan’s military regime as much as possible.

But the Korean Christians were willing to stand against Empire, even if they were standing alone. Uncle 경섭 put it simply: “In the Bible, if you worship an idol, you are against God. There is only one God.”

My Great Grandfather never attended any of the mandatory shrine worships. Uncle 경섭 wasn’t clear about how he managed to avoid the colonial government’s enforcers. But whatever the Bible said, Great Grandfather did.

It is too easy to say that Christian resistance to State Shinto was a no-brainer. But the reality was far more complex: most Christians were willing to bend the knee.

The more I retell Great Grandfather’s story, the more amazed I am by Great Grandfather’s sustained resistance to Empire. How did he maintain his integrity after decades of oppression? How did he keep praying when the world told him not to pray?

I think it all goes back to being Korean.

It wasn’t the missionaries who called Great Grandfather to the independence movement - it was the Koreans. It was the Koreans who planned to expose police brutality. It was the Koreans who faithfully attended Great Grandfather’s worship services, sustaining his faith as well.

And it was the Koreans who built a proto-liberation theology as they dreamed of freedom for their homeland. Taking the Bible literally, they applied the stories of Moses and the Exodus to their own experiences: if God could deliver the Jews from Empire, He could certainly deliver the Koreans. The Korean Christians preached sermons and spread pamphlets encouraging their countrymen to stand strong for their true king: Jesus Christ, King of Kings and Lord of Lords.

Based on the historical evidence, I believe the reason why Great Grandfather viewed the way of Jesus as a challenge to Empire was the work of the Korean Christian community.

Great Grandfather 이원근 was the first Korean Christian whose story I could be proud of. Almost. After so many years of resenting and avoiding my own ethnic community, it was hard not to interrogate the parts of his life that I disagreed with.

Like many of the Korean Christians around him, 이원근 was a Biblical literalist. For example, he refused to be a tax protester because he thought that “Give to Caesar what is Caesar’s” meant Christians needed to pay taxes. And when the Korean Presbyterians split into the conservative Yejang and the liberal Gijang, he chose to be part of Yejang.

According to his memoir, 이원근 viewed Gijang as “heresy for not accepting the whole Bible as it is written but [interpreting] the Bible by their knowledge and intelligence distorting the true meanings.”

Okay. I love my Great Grandfather, but that is a word salad. What he really meant was Gijang was being a little too vocal about using the Bible to oppose the military dictatorship ruling South Korea. The same government that Yejang supported.

So I am not surprised that 이원근 had nothing to say when the South Korean army went to Jeju island and massacred thousands of civilians. He had nothing to say when the military dictator 박정희 (Park Chung Hee) ruled the country with an iron fist for almost twenty years. And he had nothing to say when South Korean mercenaries went to Vietnam to burn down homes, take advantage of vulnerable women, and kill even more civilians.

Empire may have failed to break Lee Won Keun's spirit, but its grip was strong.

Was 이원근 really a shining example of Christian resistance? Or was he actually doing the bare minimum?

Maybe the answer is somewhere in the middle.

Maybe Great Grandfather’s story is an invitation for me to practice grace - the same grace that was denied to my autistic body so many years ago. Maybe heroes are people who do the best they can with the little that they have. Maybe I can reckon soberly with 이원근’s limitations, while still being grateful for his spiritual inheritance.

And maybe, just maybe, Great Grandfather’s story can redeem my image of Korean people.

In my personal story, the villains were Korean Christians. But in Great Grandfather’s story, the heroes were not the enlightened white Americans, not the Japanese Christians, but the Korean Christians. The same people who cheered as their children slaughtered civilians in Korea and Vietnam and many who continue to oppress LGBTQ+ people to this day.

How did my people decide to stand for Jesus and justice? And what can I learn from their example?

First: The Koreans call me to the discipline of learning from and following Jesus. I realize that discipline is a bad word in a deconstructing church, but I believe that all those prayer meetings, all those daily devotionals helped the Koreans remain grounded in relationship to Jesus and with fellow believers. They lived into Jesus’ marginality and desire for justice, and this made them prophetic.

It will be a very long time before I go back to the daily devotional model where I get up at the crack of morning and read three Bible chapters a day. But thankfully, Christian life is done in community. I do best when I am surrounded by sisters and brothers who sharpen me, as well as shepherds who care for my needs.

Who am I allowing to speak into my life? When I am walking in a disorderly way, can I trust them to remind me who I am meant to be? How do I deepen my relationship with these people?

Instead of disowning my inheritance for the pottage of assimilation and white supremacy, I want to continue pursuing my Koreanness in a way that is safe for my autistic body.

Second: The Koreans also call me toward sacrifice. Resistance is not going to be a climatic showdown between good and evil. It usually shows up as the ordinary actions of everyday faithfulness, like writing letters or leading worship. You may never march in the streets, but it’s the little sacrifices every day that decolonize your actions.

Today, Empire is alive and well. It may no longer take the name of Tennō-heika, but it might go by Amazon or Raytheon or the University of Southern California. And if I look hard enough, there are plenty of opportunities for little sacrifices that undermine Empire.

Am I going to sleep in or attend a rally to support the hundred-plus Anaheim teachers facing layoffs?3 Am I going to watch brainrot on Netflix or am I going to expand my prophetic imagination with one of the minor Prophets or Minjung Theology? Am I going to splurge on boba or am I going to donate to the student protesters calling for our leaders to divest from genocide in Gaza?4

In the spirit of discipline and sacrifice, the Koreans also call me to continue leaning into my ethnicity, even when it’s hard. To be sure, the witness of 이원근 does not erase my lifelong experiences of trauma and grief. But it does remind me that there are Koreans who do good things in the world. They’re not perfect, but they exist.

I feel a strong invitation from God to stop painting my own people with the broad brush of internalized racism. Instead of disowning my inheritance for the pottage of assimilation and white supremacy, I want to continue pursuing my Koreanness in a way that is safe for my autistic body. Right now, I’m doing this by building friendships and even practicing Korean with other Korean people from different walks of life.

And I will keep moving forward as the Spirit leads me.

Ultimately, Great Grandfather’s story inspires me to be an Asian Pacific American who loves God and loves his people. He was not perfect, but he refused to bend the knee to Tennō-heika or the Empire. 이원근 stood boldly for his true King when nobody else would, and that makes him my hero.

Today, I hope he can be your hero too.

Joseph Cho is a third-year admissions consultant who was born and bred in the heart of the Orange Curtain. He's also an incoming master's student at Emory's Candler School of Theology. When he's not dissecting clunky college essays, you can catch him testing vegan cookie recipes, blasting Lynyrd Skynyrd, or musing on everyday theology over at The Jo Cho Show. Joseph is especially excited to read, think, and write more about how Asian American Christians can witness authentically in the midst of racial capitalism.

Pronounced “Gyung Sup.”

Pronounced “Gyung Joon.”

Anaheim Union decided not to go through with laying off our teachers. Thanks be to God.

This was written when the University of California-Irvine student protesters had just set up an encampment. The police suppressed the protest about two weeks after this testimony was delivered.