By Dr. Allen Yeh, Dean and VP of Academic Affairs at International Theological Seminary.

In my last article (part 1 of 3), I talked about the tension between prioritism and holistic mission, illustrated in the Lausanne 4 theme, “Let the Church Declare [proclamation evangelism] and Display [physical witness] Christ.” But the final word in L4’s theme is “Together” which is what I will be exploring in this article (part 2 of 3). Michael Oh, the CEO of Lausanne, opened the Congress with the words “the most dangerous four words are: I don’t need you.” That resonated throughout our seven days together at L4.

Lausanne as a Global Event

When people ask me what is the big deal about going to the Lausanne Congress, other than it being a once-in-a-generation event (it happens roughly once every 15-20 years), I say that it is like the “Olympics” for Evangelical mission leaders in the sense that it is a huge global event where the top leaders converge in the same place, and also it is a huge privilege to be invited/selected.

The analogy of the Olympics is not accidental, as the city of Lausanne, Switzerland, not only birthed the Lausanne movement, but also is the headquarters of the IOC (International Olympic Committee)! And the city of Geneva, Switzerland, is the headquarters of the United Nations as well as the World Council of Churches. Switzerland, being famously politically neutral, has long been seen as the ideal place to convene global events for peace. I confess, global gatherings of harmony and unity always captivate my imagination, and I have watched—and attended—many an Olympic games (though certainly, as Paris 2024 can attest, it is a difficult task to keep everyone happy!).

Being born in 1975, I was obviously not at Lausanne I in 1974, and also I was too young to go to Lausanne II in 1989. But I was at Lausanne III in 2010, and this fourth Congress felt like a joyful reunion (there were many people I had literally not seen since the last one). Unity is indeed joyful, if it can be achieved.

Evangelicals and Ecumenical Unity

However, despite the fact that unity does wonderful things, Evangelicals are notoriously bad at it, even though the Bible not only commends it, but commands it. Why would this be? Would not the Gospel be something that Evangelicals (who have as our etymological core the evangel or the Gospel) can easily unite around? In my previous article, I unpacked how disputes over the very meaning of the Gospel has actually led to division.

Sadly, during the 20th century, evangelicalism and unity (aka ecumenism) became diametrically opposed to each other, and Evangelicals started seeing “ecumenism” as a dirty word. Outside the Lausanne 4 Congress hall, there were fundamentalist Korean protestors with signs saying “WCC/WEA spirit out!” (implying that Lausanne was capitulating to a spirit of unity which channels the World Council of Churches, or even the World Evangelical Alliance!). It is notable that the General Secretary of the WCC, Jerry Pillay, was in town “to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the National Council of Churches in Korea (NCCK) at a global conference on 20-22 September, then attend the assemblies of the Presbyterian Church of Korea Presbyterian Church in the Republic of Korea on 24-26 September” which perfectly coincided with L4’s dates of 21-28 September, but he did not make an appearance at L4. I can only surmise that the uproar would have been too great to risk it, given the protest signs outside the Congress hall. This seems to be a step backward from the third Lausanne Congress in 2010 which had 350 observers from Roman Catholic, Orthodox, and other traditions in attendance. So why do Evangelicals often think that unity/ecumenism is bad?

The history of this stems back to the Edinburgh 1910 World Missionary Conference, perhaps the most famous missions conference in church history. It became known as “the birthplace of the modern ecumenical movement,” and even though it was Evangelicals who organized it and mainly Evangelicals who attended it, many Evangelicals today look back at that event with a wrinkled nose. The reason is because of the so-called “Edinburgh Error,” which is perceived by conservative Evangelicals today as the mistake of throwing out theology for the sake of unity. There were a number of reasons why theology was not discussed, but I do not think it was for any insidious reason. One reason is because theological unity was just assumed amongst the Evangelical attendees, and they wanted to get on to the task of strategy (strategy will be the subject of my next article in this series). Another reason is because they did not want denominational differences to clog the discussions (in other words, theological hair-splitting was not the point of Edinburgh 1910; they wanted to major on the majors and not on the minors).

Whatever the reason, Edinburgh 1910 set a precedent for modern ecumenism, and the perpetuation of the false idea that “Doctrine divides, service unites” has extended even to Christians today being afraid to do evangelism for fear of offending people, whereas social justice is never found to be offensive. But what has happened is that there has been a pitting of “ecumenism” vs. “evangelicalism” becoming code words for “progressive” vs. “conservative.” This is the reason for those protest signs outside the L4 Convention hall. Ecumenists (exhibited most prominently with the World Council of Churches) are seen as favoring unity at the expense of theology while Evangelicals (represented globally by organizations such as the World Evangelical Alliance and the Lausanne Movement) are perceived to do the opposite. But in our DNA, Christians ought really to be both ecumenical and evangelical. Both the WCC and the Lausanne movement are the children of Edinburgh 1910, but unfortunately some see them as having sibling rivalry like Ishmael and Isaac being the children of Abraham.

Key Issues at Lausanne 4

That is a lot of background leading up to L4. Regarding the Congress itself, the issue of unity certainly rocked the Congress proceedings in a number of ways, which I will describe briefly here: 1) justice; 2) sexuality; 3) worship music; 4) the call for unity itself.

Justice

Ruth Padilla DeBorst, a Latin American missiologist, gave a plenary address on justice in which she called out a few current worldwide atrocities, notably Israel/Palestine, which created some back-and-forth with the Congress director David Bennett. I won’t rehash the controversy, because much ink has already been spilled on the matter, but you can read about it here and here. Her message might go down in history as being the most memorable address of the entire Congress, though perhaps not for reasons that either side would have wanted!

Sexuality

Vaughan Roberts is the rector (or “pastor”) of St. Ebbe’s Church, where I worshiped when I was studying in Oxford. He gave a wonderfully balanced talk about sexuality which was firm but compassionate. Still, this did not prevent some of those same Korean fundamentalists outside the Lausanne Congress hall holding up signs like “Protestants, protest the gay sin society” and “Protest the Homosex system,” not to mention some from within the Congress itself who felt Roberts did not come down hard enough on the LGBTQ community.

Worship

The worship music also was a major source of concern to many, especially to the Global Ethnodoxology Network who were in attendance. For a Congress which purports to be cutting-edge global, it shockingly was lacking in the diversity of song selection (L3 even did a better job, so they regressed!). The two groups who alternated leading the music were a Korean praise band, Isaiah 6tyOne, and a Northern Irish group, the Getty Band (who are famous for writing modern-day hymns such as “In Christ Alone.”) Keith & Kristyn Getty sang many of their original songs, complete with Irish fiddles, but ironically Isaiah 6tyOne mainly just sang Western songs, despite the fact that they were on their home turf of Korea, and also they are famous for their own original Korean songs (just look them up on YouTube) so why didn’t they go with those? For those who objected that it was about familiarity or ability, even Lausanne’s Younger Leaders Gatherings (YLG) had more diversity in the song choices, and global doxology has been done well in conferences such as Urbana and the Evangelical Missiological Society (EMS). The fact that L4 chose over 90% Western songs was lamentable and a head-scratching decision.

I have a theory: of all Asians, Koreans are the most likely to mimic and adore U.S. Americans, with music and the megachurch model and more. My theory is borne out by this evidence: on the fifth night of the Congress, there was an impressive multimedia presentation about the history of the church in Korea. Much of this story highlighted the atrocities of the Japanese attack and occupation of Korea in the first half of the twentieth century. At one point, they mentioned: “In 1910, Japan forcibly colonized Korea… Christian schools established by missionaries were established throughout the country… Rejecting Japanese-style education, and desiring to learn Western culture, students gathered in these schools, hoping to reclaim their country’s independence.” And there it is. Later in the presentation there was another line that said: “We remember the blue-eyed missionaries who dedicated themselves to bringing the Gospel, willing to die for the poor and lost souls of Korea.” Of all Asians, Koreans are most likely to not see America as the colonists, but as the saviors, and therefore as worth imitating. (It must be said: obviously not all Koreans are homogeneous, as the Korean integral mission group, mentioned in my last article, pushed back against the perceived overly-Western influences in the Seoul Statement).

Unity

Michael Oh’s opening plenary was very well received. His closing plenary was a bit more controversial as he used an illustration of “bees” vs. “flies” and urged us to be the former and not the latter, namely to seek beauty and not filth. Some thought it was lovely and moving, others thought it was toxic positivity and glossed over hard things.

Conclusion: Unity in Mission—A Biblical Call

Regardless, togetherness is not easy, and it is often bought with a price. But the price ought not to be a compromise in the Gospel. It should, however, be at the cost of our pride. To be fair, Oh did highlight again and again that we ought to be characterized by HIS: Humility, Integrity, and Simplicity.

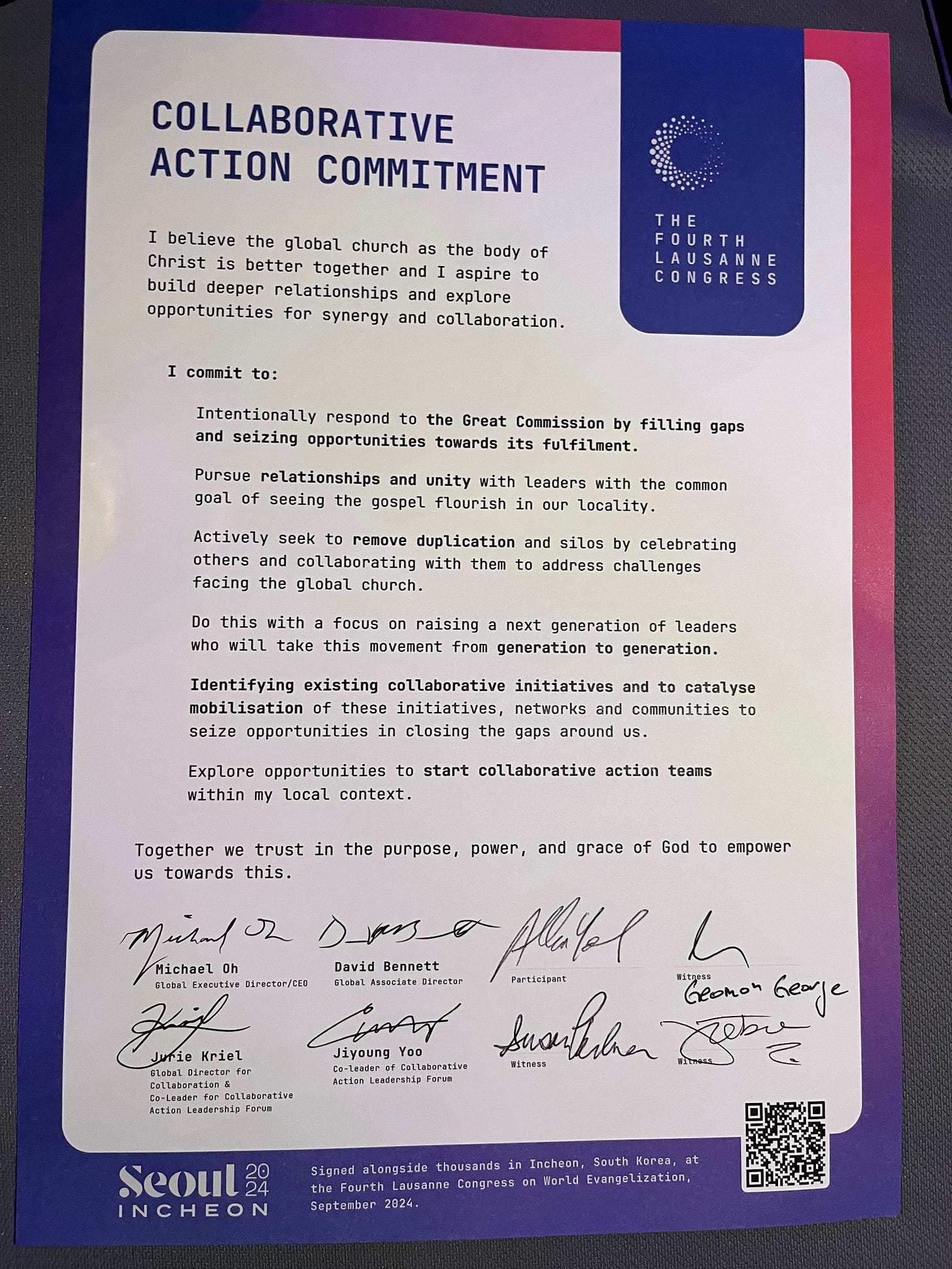

If there was one word that seemed to be the most-repeated at L4, it was “Collaboration.” Every afternoon of the Congress, everyone gathered together in Collaborative Action Teams, and arguably this was the most important part of the entire Congress—not the plenaries. Because if the last word of the Congress theme was “Together,” indeed Collaboration is just that: working together. And maybe more important than the Seoul Statement was the Collaborative Action Commitment which everyone signed on the last day, to pledge to work together moving forward. That seemed to be something that everyone could sign. Every delegate at L4 was put in a table of 6 for the duration of the Congress, and my table—a brother from Pakistan, another from Korea, a sister from Nigeria, a brother from India, and a sister who is Jewish American, and me—all signed each others’ Commitment cards.

Michael Oh previously used a pop culture reference to describe the function of Lausanne. Anyone familiar with the Marvel Cinematic Universe knows that the Avengers each had solo adventures but it was Nick Fury who brought them together in the same room to form a team. Lausanne, says Oh, is the “Nick Fury of missions.” It is not a superhero itself, but it unites the superheroes (in this case, missionaries) who are doing the amazing work out on the field. And more can be done together than apart. In my book Polycentric Missiology, I made a similar analogy, except with a classical illustration: Lausanne is like the Medici family, patron of the arts, who brought together amazing artists, poets, scientists, and writers, such as Michelangelo, Leonardo de Vinci, and Botticelli, etc., and when all these people convened, it launched a movement that changed the world: the Renaissance. The Medicis were not artisans themselves, but they were catalysts, and the Renaissance could not have happened without them. Lausanne functions in such a way for the Evangelical world (given that we do not have unity under the Pope like Catholics, for example), although to be fair there are other Evangelical organizations which also function similarly, like the WEA or INFEMIT (the International Fellowship for Mission as Transformation). But Lausanne might be the biggest.

Let me speak to my Evangelical family for a moment: for those of us who say that correct theology is of the utmost importance and unity is liberal concession, let us not forget that the Apostle Paul admonishes us:

“If I speak in the tongues of men and of angels, but have not love, I am a noisy gong or a clanging cymbal. And if I have prophetic powers, and understand all mysteries and all knowledge, and if I have all faith, so as to remove mountains, but have not love, I am nothing.” (1 Cor. 13:1-2; and I would say to the ecumenists that they need to focus on v. 3).

After all, love God and love neighbor are the first and second greatest commandments. And the Cape Town Commitment focused on love as its theme, as is right and proper (sidebar: the Apostle’s Creed and the Nicene Creed shockingly say not a word about love even though it is arguably the most important theme in Scripture, and this is why we need to continually update our theology). And it is not just Paul, Jesus himself prays in his High Priestly Prayer about all Christians:

That they may all be one, just as you, Father, are in me, and I in you, that they also may be in us, so that the world may believe that you have sent me… I in them and you in me, that they may become perfectly one, so that the world may know that you sent me and loved them even as you loved me. (John 17:21, 23).

In essence, Jesus wants Christians to be unified as tightly as the Father and the Son are unified, and that unity will be a sign to the world that Jesus is true. To state it in the opposite way: when Christians are disunified, it makes the world disbelieve that our Gospel message is authentic.

This is why the Lausanne movement aims to do something rare indeed: unify Evangelicals (who infamously love to spar over doctrine) in one accord for the purpose of uniting in missional love. It is mission which is the mother of ecumenism, to allay the fears of those who lay the blame at the feet of anemic theology. The British missionary Lesslie Newbigin—one of the most significant missiologists of the 20th century—had as the core of his thought that “the action of the eschatologically aware church must be both in the direction of mission and in that of unity, for these are but two aspects of the one work of the Spirit.”

Much is made about the “Spirit of Lausanne.” I joked that maybe the Spirit of Lausanne is actually disagreement! But in all seriousness, it is unity—which is abundantly necessary. However, it is unity in diversity not unity in uniformity—this is the beauty of the Evangelical global body, and it is what we will see in heaven with the vision of Rev. 7:9, “a great multitude that no one could count, from every nation, tribe, people and language, standing before the throne and before the Lamb.”

Dr. Allen Yeh is Dean and VP of Academic Affairs at International Theological Seminary located near Los Angeles. He earned his B.A. from Yale, M.Div. from Gordon-Conwell, M.Th. from Edinburgh, and D.Phil. from Oxford. Allen has been to over 60 countries on every continent, to study, speak at conferences, do missions work, and experience the culture. He is also the author of Polycentric Missiology: 21st Century Mission from Everyone to Everywhere (IVP, 2016), and co-editor (along with Tite Tienou, former Dean of Trinity Evangelical Divinity School) of Majority World Theologies: Theologizing from Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the Ends of the Earth (William Carey, 2018).